CNN

—

The escalating drive from President Donald Trump and other Republicans against programs to promote greater diversity in education and employment is on a collision course with fundamental changes in the nation’s demographic make-up, particularly among the young.

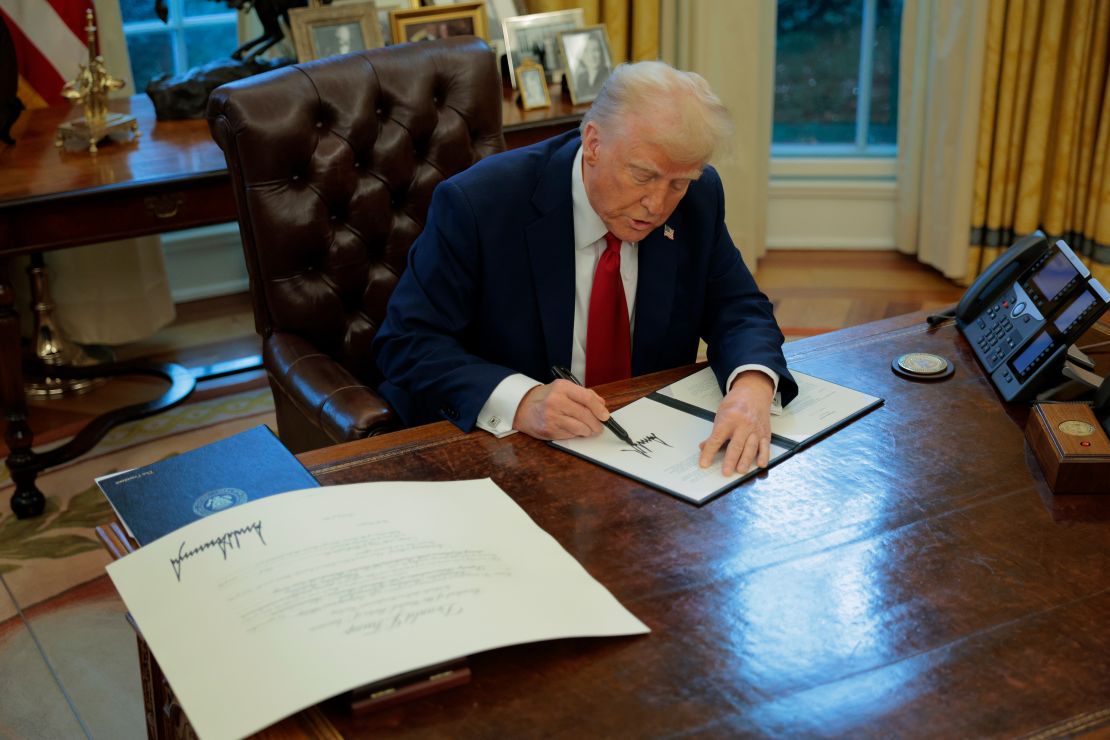

Conservative opponents of diversity initiatives have clearly seized the momentum in the policy debate. In 2023, the six Republican-appointed Supreme Court Justices joined in a decisive ruling to virtually eliminate the consideration of race of college admissions. Since taking office, Trump has followed with a flurry of executive orders to end “diversity, equity and inclusion” programs within the federal government and to penalize private employers that utilize them — even to the point of potentially seeking criminal prosecutions. Facing this pressure, prominent companies in recent months have publicly renounced efforts to increase diversity in hiring or contracting. Democrats have been tentative and divided over how hard to push back against the conservative drive to eradicate the so-called DEI programs.

But this diversity counteroffensive is advancing precisely as kids of color have become a solid majority of the nation’s youth. Since the start of the 21st century, young Whites have been rapidly declining not only as a share of the overall youth population, but also in their absolute numbers — to an extent possibly unprecedented in American history. This tectonic reshaping of the American population means that demography, not Democrats, will likely emerge as the biggest obstacle to Trump’s campaign to uproot DEI programs across US society.

These demographic trends ensure that in the years ahead, the nation will increasingly rely on non-White young people as an increasing portion of its students, workers and taxpayers. Yet today, minority young people remain tremendously underrepresented at the most exclusive colleges and universities and in high-level, well-paying jobs across the private sector.

Abandoning diversity programs even as the nation continues to grow more diverse could expose US society to two distinct risks. One is that as minorities make up a growing share of the future workforce, failing to equip more of them with advanced academic and technical skills could leave the nation short of the highly trained workers it will need as it transitions further into the information-age economy.

“The future of the nation’s labor force productivity and economic well-being will rely heavily on the success and integration of today’s and tomorrow’s increasingly multiracial younger population,” William Frey, a demographer at the center-left Brookings Metro think tank, wrote recently.

The other big risk is that under current trends the US could harden into a more overtly two-tier society, with a widening gap between the growing overall presence of minorities in the population and their limited representation in the most prestigious educational and employment opportunities. That could be a formula for even more social turbulence and alienation than the US has already experienced around current racial disparities.

The pushback against diversity programs “is an attempt to entrench racial discrimination and disparities at every level of society and to horde power and influence among what will soon be a minority population of White people and the wealthy,” said Janai Nelson, president and director-counsel of the Legal Defense Fund, a leading civil rights organization.

“Relegating … marginalized groups to second-class citizenship will upend the American experiment of multiracial democracy and reinstate a caste system — and that is the point. Indeed, if unchecked, these efforts will create levels of disenfranchisement and disillusionment yet unseen in our modern history,” Nelson said.

Opponents of diversity programs argue there’s no reason for concern even if White people hold on to most of the prestigious educational and employment opportunities as their overall numbers shrink. “I think we need to get away from being concerned about the skin color of those who are occupying those positions,” said Jonathan Butcher, a senior fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation. “I think we need to move to a point where we are concerned about what the individuals accomplish once they are there.”

But civil rights advocates argue Trump and his allies are brewing a recipe for both social and economic strain by hobbling efforts to expand opportunities for minorities exactly as they represent more of the nation’s future workforce. To these critics, the drive by Trump and his Republican allies to dismantle diversity programs at this transitional moment amounts to raising the castle walls of privilege against a rising tide of demographic change.

“If institutional gatekeepers don’t ensure equal access to opportunity, this country will become even more dangerously stratified by race and future generations of Americans will be wholly incapable of meeting the challenges of an increasingly global landscape,” said Nelson. “This is a recipe for disaster.”

In this century, the change in the demographic composition of America’s youth population has been swift and sustained. Kids of color increased their share of the nation’s total under-18 population from 39.1% in 2000 to 51.6% in 2023, according to an analysis of Census Bureau data provided to CNN by Frey.

This change has been broadly felt. Over that period, the minority share of the youth population has increased in all 50 states, according to Frey’s calculations. In 18 states, kids of color already constitute more than half of the youth population. In six other states, minority kids make up at least 46% of the youth population, suggesting they will become the majority group before long.

The change in the absolute numbers of the youth population may be even more revealing than these shifts in its proportions. Since 2000, the number of non-White kids has increased by just over 9.3 million, Frey found. Over that same period, the number of White kids has declined by nearly 8.8 million. In 47 of the 50 states, not only has the share of Whites younger than 18 declined since 2000, but so has their absolute number. The only states that have more White kids today than at the turn of the 21st century are Utah, Idaho and South Carolina — and even they have seen only small increases, totaling about 120,000 between them. By contrast, 30 states have at least 75,000 fewer White kids today than they did in 2000.

Frey has calculated from Census data that the number of White kids shrank from 2000 to 2010 and from 2010 to 2020, and continued to fall from 2020 to 2023. He says there is likely no precedent in American history for such an extended decline in the number of White young people. Something similar may have happened “during the Great Depression for a few years,” Frey told me. “That’s possible. But for most of our history as a country we’ve been growing. It’s fair to say that this is the first time we’ve seen a decline like this for this length of time.”

Nor does Frey see much possibility that the decline in both the share and absolute number of White kids will reverse any time soon. “I don’t see this decline reversing, because the White population is older and women in their child-bearing ages are getting to be a smaller share of that group,” Frey told me. Immigration, he adds, isn’t likely to add many more White kids since most legal migrants, come from predominantly non-White countries. The Census projects the minority share of the youth population will reach 53% by 2030 and 60% by 2050.

All of this guarantees that non-White kids will represent the principal source of workers for the 21st-century economy. As recently as 2000, White kids still represented nearly 70% of all high school graduates, according to the federal National Center for Education Statistics. But in the 2021-22 school year, young White people, for the first time, fell below the majority of high school graduates (at 49.4%), and their share has continued to tumble: The National Center projects that Whites will slip to 46% of all high school graduates next June and to as little as 43% of the graduating class in 2031. The NCES projects that 300,000 fewer White kids will graduate high school this year than in 2008.

Enrollment in postsecondary education is moving along the same track. The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce reported in a study last year that the number of White students attending colleges and universities plummeted by 375,000 from 2009 to 2019, the latest year for which they calculated detailed figures by race; the number of Black students tumbled by nearly 100,000 as well. All the growth in postsecondary attendance over that period came from Latino students (up about 190,000) and, to a much lesser, extent Asian Americans (up nearly 20,000).

Yet kids of color continue to face systemic inequities at each stage of the journey from education into the workforce. Research, for instance, has consistently shown that student performance lags in elementary and secondary schools where poverty is pervasive; today, about three-fourths of Black and Latino students, compared to only about one-third of their Asian American and White counterparts, attend schools where at least half of students qualify as poor under federal definitions, according to the National Equity Atlas published by PolicyLink, a research and advocacy group, and the Equity Research Institute at the University of Southern California.

Higher education likewise remains substantially stratified by race. About two-thirds of both Black and Latino students, Georgetown found, attend so-called open-access colleges, which are the least competitive in admissions and spend less than half the money and employ less than half the faculty per student as more selective schools. Though Black, Latino and Native American students have grown to 37% of the total postsecondary student body, they hold only 21% of the seats in roughly the 500 most selective schools. White and Asian American students, by contrast, still constitute nearly three-fourths of all those attending the most selective institutions, the Georgetown center found, far beyond their three-in-five share of the total postsecondary student population. While about four-fifths of students at the selective colleges finish their degrees, that’s true for less than half of those at the open-access institutions.

“Open-access institutions educate the vast majority of college students, but, unfortunately, do so with the fewest resources and have the lowest success rates,” the Georgetown Center concluded in its 2024 report. “The American postsecondary system, in other words, tends to provide the highest-quality education to those who need it least: students who are primarily wealthier than the median and who attended well-resourced high schools that smooth the transition into the most-selective colleges.”

This pipeline of educational inequality ultimately terminates in widely unequal outcomes in the job market. The average hourly wages of Black and Latino workers remain about 11% lower than the wages for White workers — a wider gap than in 1979 for both minority groups, according to an analysis of federal data by the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank. Ben Zipperer, an EPI senior economist, has calculated that although Whites make up about 58% of all workers, they represent 68% of those whose wages put them in the top fifth of highest earners. Black and Latino workers, though nearly one-third of all workers, are just a little more than one-sixth of those at the top, wage-wise.

Nelson of the LDF points to other measures of enduring inequality. Across the 100 largest companies listed on the S&P stock index, Black, Latino and Asian Americans hold less than one-fourth of upper management jobs, according to a Harvard Law School analysis.

“Black and Latinx people,” she added, “make up fewer than 1% and 2% of Venture Capital entrepreneurs, respectively, according to a Harvard Business School analysis.” Despite some gains, women remain significantly underrepresented on both fronts, too, she noted. Though women obtain about 60% of all four-year undergraduate degrees and nearly two-thirds of all post-graduate degrees, the Harvard Law analysis found they hold only slightly more than one in four of those upper management jobs in large companies, little more than racial minorities.

Less precisely quantifiable, but potentially just as important, these educational inequities also yield enduring racial disparities in what could be called the C-suite of American life —the positions that wield decision-making power in our major public and private institutions. Zack Mabel, director of research at the Georgetown Center, notes that the elite universities where Black and Latino students remain systematically underrepresented have long functioned as the conveyor belt producing most of the people who occupy those roles.

“There’s so much concentrated power in decision making that grows up out of these selective institutions and as a society I would argue we are in desperate need of diversifying access to those bastions of power,” Mabel said. “The only realistic way we are going to do that is by diversifying our selective institutions.”

Despite these entrenched disparities, polls for years have shown that most Americans, including many racial minorities, express opposition to “affirmative action” or diversity programs that explicitly elevate racial considerations above ostensibly neutral concepts of merit in employment or college admissions.

And after a campaign in which Trump relentlessly attacked diversity efforts, his election day gains compared to 2020 among Latinos, Asian Americans and Black men, demonstrated at the least that his hostility to such programs was not a deal-breaker for many non-White voters.

Daniel Cox, director of the Survey Center on American Life at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, said Trump’s gains with non-White voters didn’t surprise him. Trump’s improvement on that front showed that the argument over diversity programs “is part of the elite discourse that working- and lower-middle-class families of color typically aren’t that bought into,” Cox said. “Your average working-class kid, the idea of going to Harvard is like the idea of going to the moon. It’s a long shot; that’s not the thing that is going to be life-changing or game-changing for them. Better opportunities where they live, cheaper housing where they live, lower crime — those are the things that are going to be game-changing for them.”

Manuel Pastor, director of the Equity Research Institute at USC, agreed that Trump’s gains with minority voters came in part because diversity programs in education and employment don’t “always reach working-class people of color in real, concrete material ways.” And Pastor believes that the backlash against diversity programs intensified because too many morphed into formulaic workplace trainings that “became often more symbolic and about discourse and how about how people feel than they were about recognizing historic disparities and giving people a leg up into the workplace.”

But, Pastor argues, none of that erases the core demographic reality that the US will increasingly rely for its future workers on kids of color who are on the wrong end of compounding disparities in educational and employment opportunity. Abandoning diversity programs now, he argues, “means wasted talent. It means lost Einsteins. It means not investing in the productivity that we need for the future.”

Like other critics of diversity programs, Butcher, the Heritage Foundation senior fellow, argues that trying to channel more minority students into elite educational institutions “is a dangerous policy to engineer from the top. I think there is no centralized control or bureaucracy that could effectively engineer those kinds of outcomes without serious unintended consequences.” Even if the rollback of diversity programs widens the gap between White and non-White young people, Butcher said, “I don’t believe that just because there would be different outcomes for individuals based on race that it necessarily represents racism.”

Amid the furious counteroffensive against diversity programs from conservatives wielding such arguments, defenders of these efforts are likely to shift their arguments over time more from equity to economic grounds.

One of the defining demographic realities of modern America is the enormous racial divergence between America’s youngest and oldest generations, a dynamic Frey has called the “cultural generation gap” and I’ve described as the contrast between “the brown and the gray.” Even as minorities have grown into a majority of the youth population, and advance toward becoming most of the working-age population, about three-fourths of seniors remain White (primarily because the US virtually shut off immigration from 1924 to 1965).

This racial transformation has been occurring even as the number of seniors, as Frey has documented, has been growing more than nine times as fast as the working-age population. That means, to pay the payroll taxes that fund Social Security and Medicare, a rapidly growing population of White seniors will depend on a workforce that is increasing only modestly in numbers but rapidly becoming more diverse.

That creates a shared interest across racial and generational lines that is rarely discussed in American politics. If kids of color continue to face the educational disparities evident today, the danger isn’t just that the economy overall will face shortages of skilled workers as those kids become a larger share of the future workforce. Ultimately, the mostly White senior population also needs more kids of color to ascend into well-paying jobs where they can be taxed to meet the growing cost of the big federal programs for the elderly. Ending diversity programs now increases the risk that the US will fail to produce as many skilled minority workers as it needs on both fronts, advocates argue.

“The people we overlook for investments is going to shipwreck the future for America writ large, but especially for a whiter, older retired population that is counting on this (diverse) younger population to contribute” to their retirement costs, Pastor said.

Frey said that sooner or later, the US will recognize that it must open more educational and employment opportunities for non-White young people because there simply will not be enough White kids available to fill all the skilled jobs the economy will demand. “To talk about getting rid of DEI is just being blind to demography,” Frey says. “Sooner or later, we are going to run out of (White) people even in those top jobs.”

In the meantime, though, the politics of diversity are now moving in the opposite direction of the demographic and economic imperatives of an irreversibly diversifying nation.