CNN

—

Americans have grown accustomed to dramatic shifts in policy each time control of the White House changes between parties. But across a wide range of domestic and foreign policy issues, President Donald Trump is now pursuing structural changes to the federal government that could prove very difficult for the next Democratic president to undo.

On many fronts, Trump is seeking not just to reduce spending or to roll back regulation, but to hollow out the federal government’s institutional capacity to influence events both domestically and internationally. Far more aggressively than in his first term, Trump is unraveling many of the key mechanisms Washington for decades has used to advance its goals.

Together with Elon Musk and his Department of Government Efficiency, the Trump administration has sought to rapidly deconstruct governmental power through, among other approaches, massive reductions in the federal workforce; the sale of federal buildings; the complete elimination of federal agencies; and the cancellation of grants that sustain extensive networks of nonprofit humanitarian organizations overseas and sophisticated academic research institutions at home.

“We’ve never, ever seen anything that has amounted to a disinvestment in federal capacity like this,” said Donald Kettl, the former dean of the University of Maryland School of Public Policy and author of multiple books on the federal bureaucracy. “We have never seen in the history of the country an effort to deliberately try to destroy so much existing infrastructure … with so little regard to what the impact is.”

To the extent Trump succeeds in his drive, he will constrain the options available to his successors. Experts agree that even a future Democratic president committed to restoring a more active role for Washington would face a yearslong struggle to replace fired agency experts, reopen academic research labs shuttered by the loss of federal funding, or find humanitarian partners abroad to replace those incapacitated by canceled contracts today.

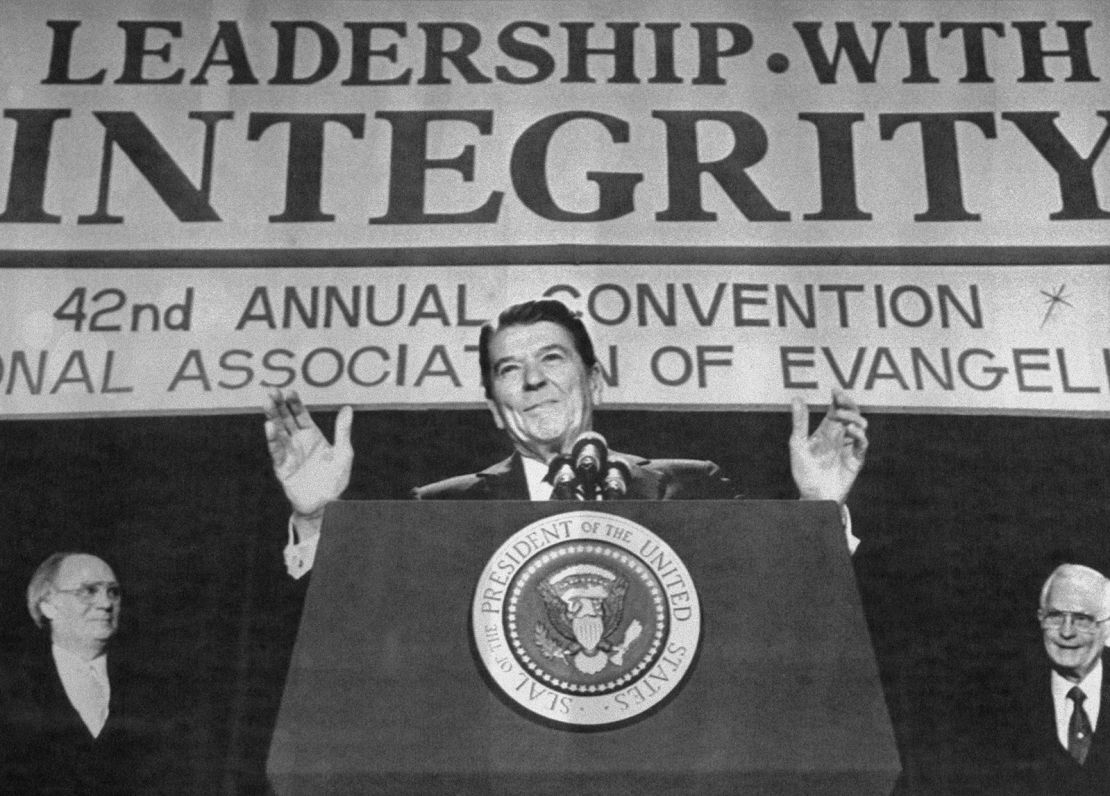

For all these reasons, some conservatives believe Trump’s offensive against the “administrative state” could secure a more lasting retrenchment of the federal government than even the vaunted “Reagan Revolution” a generation ago. “This is a bigger deal, it will be a bigger deal,” said longtime conservative leader Grover Norquist, who founded his organization Americans for Tax Reform to push for lower federal taxes and spending during Ronald Reagan’s presidency in the 1980s. “It’s not a criticism of Reagan, but lots of things have changed.”

In the Bible and other accounts of antiquity, when ancient civilizations conquered and razed cities, they sometimes spread salt on the remains as a warning and curse against those who might try to rebuild. Trump’s attempt to liquidate the federal government’s capacity in a manner this difficult to reverse might be best understood as his way of salting the earth around Washington, DC.

Each time the White House has changed partisan hands in recent years, the new president has signed a flurry of executive orders undoing those signed by his predecessor. President Joe Biden, during his first days, undid dozens of executive actions Trump had taken during his first term – just as Trump, beginning his term in 2017, reversed many of President Barack Obama’s executive decisions. Trump has extended the pattern in his second term by quickly overturning dozens of Biden actions.

Many of these changes have settled into a predictable rhythm. Originally adopted under Reagan, for instance, a ban on organizations that receive US foreign aid performing or providing counseling about abortion – the so-called Mexico City policy – has been lifted by every Democratic president, and reimposed by every Republican president, since Bill Clinton in 1993.

But in Trump’s second term, he has quickly barreled past these familiar boundaries. To borrow from Daenerys Targaryen in “Game of Thrones,” Trump’s aspiration seems not so much to spin the wheel as to break the wheel.

Foreign aid offers one measure of his intent: Not only did Trump immediately reinstate the Mexico City policy, but DOGE has eviscerated the US Agency for International Development, firing most of its staff, cancelling over 80% of its contracts, and ending the agency’s independent status by relocating its diminished remains into the State Department. (A federal district court judge on Tuesday ruled that Musk’s actions “likely violated the US Constitution.”)

The environment offers another telling indicator. During his first four years, Trump significantly weakened the regulations Obama had developed to require motor vehicles and power plants to reduce their carbon emissions, which are linked to global climate change.

But in that first term, Trump did not seek to shatter the legal bedrock beneath those regulations: the so-called “endangerment” finding that the EPA issued in 2009 under Obama concluding that carbon emissions constituted a threat to public health and the environment.

Since then, the EPA’s 2009 endangerment finding has become “the scientific and legal foundation for 15 years of Clean Air Act standards to cut climate pollution from cars and trucks, power plants, oil and gas drilling, and other industries,” David Doniger, a senior attorney and strategist in the climate and energy program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, wrote recently. “If it is repealed, those standards could all be dead.”

Trump’s first-term EPA administrators refused to reopen the endangerment finding even when conservative critics petitioned them to do so. But last week, EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin announced the agency would formally reconsider the decision and all the subsequent carbon regulations that rely on it.

Doniger, like many environmental activists, believes that amid all the evidence of extreme weather linked to climate change, the EPA faces an almost impossible task to produce a finding that could stand up in court if it tries to argue carbon emissions do not threaten public health and the environment. But, Doniger said, just reopening the endangerment finding in a way that requires a future administration to restore it would create another time-consuming hurdle to climate action.

“They want to … make it either impossible, or just an order of magnitude harder, for the next administration that acknowledges reality and wants to address climate change to do so,” Doniger said.

The changes from the Trump administration that may prove most difficult to reverse are his massive firings of federal workers and upending of federal support for research at colleges and universities.

The Musk-led DOGE effort has already led to the dismissal or departure of thousands of federal employees, including many with highly specialized expertise.

Kettl, the former public policy dean, says that a future president committed to restoring the government’s capacity in these areas will find it extremely difficult to do so. “A lot of what the federal government does is by definition large and complex,” Kettl said. “That means it is a lot harder to just go out and find the people on the street with the skills you need.” One consequence of the cuts, Kettl predicts, may be to make the federal government more dependent over time on private contractors to deliver basic services.

In an interview, Neera Tanden, who was White House domestic policy adviser under Biden, offered a pointed example of the lasting impact these personnel reductions could have. After the floods in Asheville, North Carolina, last fall, she said, the Biden administration quickly discovered that the disaster had disrupted a factory responsible for producing most of the IV bags used in American medicine for patients requiring intravenous fluids.

Within days, Tanden said, the administration had created a task force to supervise the emergency importation of “the proper IV bags” from other countries. The task force relied primarily on personnel from the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), a division of the Health and Human Services Department that leads the public health response to emergencies and disasters. But, she noted, ASPR has been among the HHS divisions already facing significant firings and dismissals under Trump.

Over her White House years, Tanden said, her experience was that career staff at agencies across the government sometimes “were persnickety, but we had people who had been there 20 years who knew how to solve problems very quickly. And that is going to be a big loss.”

The disruption could be as lasting in the nation’s capacity to conduct basic scientific research. Though the federal government directly employs over 200,000 scientists and engineers, since the Sputnik era in the 1950s it has pursued its efforts to promote advanced research largely through grants to colleges and universities. An annual survey last year found that federal dollars account for 55% of the total $109 billion universities and colleges spent on scientific research, with that share rising even higher for some highly specialized fields.

This academic partnership with the federal government has produced generations of scientific, engineering and health care breakthroughs affecting every aspect of modern life, from computers and the internet to new drugs and cancer treatments. But the moves by Trump and Musk threaten to stall that assembly line.

By canceling grants – and slashing how much of them recipients can use to fund ongoing expenses – the administration is not only terminating specific projects, but also weakening the capacity of academic institutions to conduct future research, many experts fear. As scientific grants are rescinded, some universities are reducing the number of graduate and PhD students they admit; others may reconsider decisions to invest in new laboratories or other research facilities, said Joanne Padrón Carney, chief government relations officer at the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Once schools decide not to build those facilities, or to admit those students for advanced study, rebuilding that pipeline of talent and infrastructure will take time – even if a future president reopens the spigot of federal research dollars, she said. “What history has shown us is that it’s easy to dismantle areas of science and technology,” Carney said, “but it’s difficult to rebuild.”

Even this doesn’t exhaust the list of structural changes Trump and his congressional Republican allies are seeking. He has signaled that he may try to end the independence of the Postal Service and fold it into the Commerce Department or privatize it, though he does not appear to have the legal authority to do either. Congressional Republicans are seeking not only to revoke the specific federal waiver that California has used to require auto companies to move toward electric vehicles, but to completely eliminate California’s authority to set its own clean air standards – which it has wielded since 1967. Led by Senate Republicans, Congress is exploring ways not only to extend the tax cuts passed under Trump in 2017 but to make those reductions permanent, which would indefinitely reduce the revenue available for a future Democratic president to devote to federal programs.

Looking across all of this, Norquist, the longtime activist, sees a new peak in the conservative drive to constrain Washington. Norquist is probably the most visible conservative advocate for reducing the size of the federal government. He famously once said, “I don’t want to abolish government. I simply want to reduce it to the size where I can drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub.”

Reagan, who declared in his first inaugural address that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem,” has long been the patron saint of small government conservatives.

But Reagan had only mixed success in restraining the growth of government. The tax cuts he passed in 1981 did permanently lower the top marginal tax rates and cut a mold that Republicans followed for further tax cuts under President George W. Bush and Trump. But Reagan was mostly unsuccessful in his attempts to make major reductions to federal spending programs.

Norquist said he believes Reagan was at least as committed as Trump and Musk to shrinking government. The difference, Norquist argued, is that after decades of organizing by conservative activists, the institutional forces around Trump are more receptive to that goal. “I don’t see a different level of ambition,” Norquist said. “I see a different level of capacity.”

Under Reagan, he said, Republicans never controlled a majority in the House of Representatives. And while they did control the Senate for his first six years, their majority included many moderate GOP senators resistant to Reagan’s agenda. Most Republican governors then were likewise hostile to big cutbacks in federal programs, he noted, and the Supreme Court, though operating with a GOP-appointed majority, was also more centrist. Elected Republicans were more reluctant to cross career federal employees in those years too, Norquist said.

For Trump, the political dynamic is more favorable on each of those fronts, Norquist argued. “You start with a House and Senate that shares the president’s commitment to tax less, spend less, grow more and regulate less … and a Supreme Court that is not trying to trip you up and a bureaucracy that they no longer defer to,” he said. Trump’s pugnacious approach to politics matters too, Norquist said. “Trump has a personality that faces adversity and does not blink,” he said.

Norquist sees the sweeping reductions Trump and Musk are imposing on federal agencies as only an initial stage. Eventually, he argues, the GOP must seek to convert the major federal programs for lower-income families, including Medicaid and food aid, from open-ended entitlements into block grant programs with fixed appropriations . “You don’t have to do everything right now,” Norquist said. “You have to govern to make things better to get the right to win the next election to continue to govern.”

Tanden sees the fight that Trump has triggered over Washington’s role in similar generational terms. She believes that Trump, and key advisers such as Musk and Office of Management and Budget director Russell Vought, are seeking to permanently disable the federal government’s capacity. “They fundamentally believe that the agencies of the federal government and the people who work in them are (obstacles) to their libertarian fever dreams,” Tanden said. “So, they want to slaughter these agencies.”

But while Norquist believes Trump’s initial steps will generate enough public support for him to push further, Tanden is cautiously optimistic that his efforts will trigger a backlash that protects many of the programs he’s targeting. That, she notes, is what happened when Trump in his first term tried to repeal Obama’s Affordable Care Act: During that fight, the program became more popular with the public than it ever had before and that popularity has only increased since.

“It’s not a minor fact that he tried to destroy the ACA, he was foiled, and the next president (Biden) comes along” and significantly expands coverage under the program, Tanden said. “And that was not controversial at all because the ACA had become popular, so expanding it had become popular.”

The same trajectory, she said, could unfold for many of the government services Trump is dismantling today. “He breaks things and the question is: does the public basically go along with breaking it or can you make clear to the country and the public that this is something that should not be broken?” Tanden said.

The answer to Tanden’s question could go a long way toward deciding which party gains the upper hand among voters as Trump continues his campaign to raze key pillars of federal power – and then salt the earth over the remains.