CNN

—

After months of wrestling with the decision of whether to run for reelection for a third term in the swing state of Michigan, Sen. Gary Peters took a pass.

At a moment when Senate Democrats are grappling with how to win back voters they lost to Trump in 2024, Peters was the first of at least three Senate Democrats who have opted against running for another term in the Senate, citing in part the changes to a body that used to be much easier to make deals in.

“I will say, over these last few years, it gets harder every single year,” Peters said in an interview in his Washington office last week. “The middle is disappearing.”

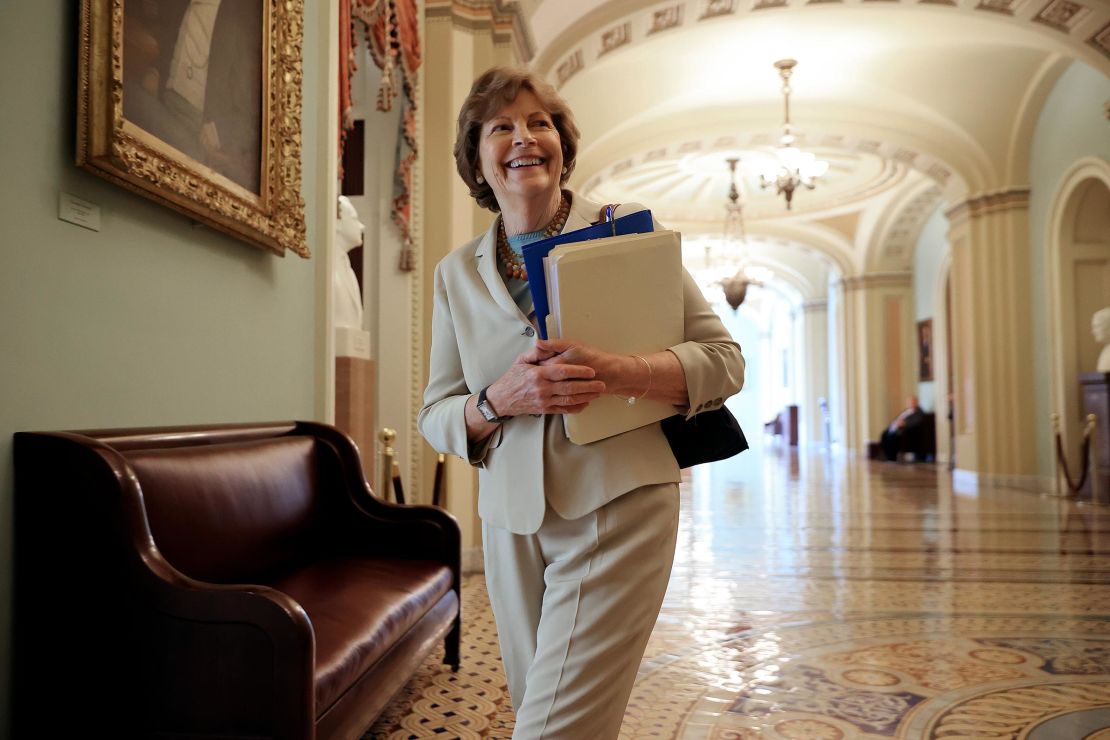

The retirements of the three Democratic senators – Peters of Michigan, Tina Smith of Minnesota and Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire – illustrate the challenges Democrats face out of power. They also reflect the broader problems of the institution, which had already grown less collegial and productive even before it allowed President Donald Trump’s new administration to usurp its authority on everything from spending to tariffs.

The senators leaving aren’t the same. Smith is proudly liberal, while Peters and Shaheen skew decidedly more toward the middle. Shaheen is a decade older than Smith or Peters and has been in the Senate longer. But all three have been instrumental in quietly toiling away on bipartisan negotiations and have earned a reputation for working across the aisle and away from the spotlight.

They’re leaving a more divided place where the middle of both parties has been eroded and each year, big bipartisan legislation seems a more elusive goal.

“It’s not just gotten more partisan, but the base has gotten to the point where, if you work with the other side, that’s considered by some to be a negative character, character trait of what people are doing. And, and that’s a really bad position for us to be in,” Shaheen told CNN.

More departures could be on the horizon, too: Sen. Michael Bennet of Colorado is eyeing a run for governor in 2026 instead of running for reelection in the Senate.

In less than a decade, the Senate has seen a host of dealmaking lawmakers from both sides of the aisle retire or lose reelections. In the last cycle alone, Democratic Sens. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia retired. Sen. Jon Tester, a Democrat from Montana, lost in a state Trump took by 20 points.

Republican senators who built reputations for sometimes bucking their party and Trump have also fled Washington. Sen. Mitt Romney, a Republican from Utah who helped negotiate the infrastructure deal, opted not to seek reelection in 2024. Republicans Sen. Rob Portman retired in 2022 citing the brutal commute and a feeling that gridlock was getting worse in Washington.

Interviews with the three Democrats who will leave at the end of next year, as well as multiple current and former senators, reveal that the Senate has become a body where, too often, a willingness to negotiate and compromise is attacked and senators’ incentives to be louder and more partisan have only grown.

“We’re getting to a place where people are coming here ready to fight rather than ready to legislate,” said Sen. Angus King, a Maine independent who caucuses with Democrats. “I think it’s a problem that we are losing the middle. In fact, ironically, it’s the main reason I ran last time, because I felt that we are losing the middle, and you can’t get things done without people that will listen to both sides try to find solutions.”

During Trump’s first term, a group of senators found an avenue to cut deals on a series of packages to protect the country’s economy amid the once-in-a-generation pandemic. Under President Joe Biden’s, the Senate reached agreement on a massive infrastructure deal and bipartisan legislation on semi-conductors.

This year, there’s simply no big dealmaking to be found, and even funding the government — a function of Congress considered the bare minimum — barely got done in March (and that bill was just a continuation of funding levels from the Biden administration).

Current and former senators say part of the change in the Senate is the fact that the country has become more polarized. Campaigns are bitterly fought, and incumbent lawmakers have to fear being primaried by their base as much as opponents from the opposing party.

That atmosphere has given senators fewer incentives to stick around Washington, particularly for Democrats, whose path to regain the majority in 2026 is a longshot. The three retirements make that road even tougher, creating three open races in seats where the incumbents likely would have had a key advantage.

The departures of incumbents also comes at an uncertain time for the party at large. Democrats have struggled in the minority to combat Trump’s rapid dismantling of the federal government, his tariffs, his mass deportation policies and even his plans to renew massive tax cuts in his second term. Democrats have little leverage to fight back as the party’s base is growing more and more impatient with their inaction.

“They are craving the understanding that we get this is not normal. These are not normal times, and I think we need to listen to that and not just patronize people by saying if you only knew what I knew then you wouldn’t feel the way you feel,” Smith said. “That’s why people don’t like us.”

But while Smith voted against a plan to keep the government funded in March as the base was clamoring for Democrats to stand up to Trump, Shaheen and Peters voted with Republicans and Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer to keep the government’s lights on – a decision that infuriated some Democrats.

“One of the things I learned as governor is that you don’t have the luxury of saying, ‘I’m not going to work with this person and I’m not going to solve this problem.’ When you’re in charge, it’s your responsibility to help figure out how to get it done,” Shaheen said.

Pressed on the fact that most of her caucus didn’t agree this was one of those moments, Shaheen was frank.

“I disagree with them,” she said. “I think they weren’t thinking about what the seriousness of the alternative was, to have a government shutdown. And then there was no guarantee that we could ever open the government up.”

In the next several months, Democrats will have to coalesce around a unified message ahead of the midterms and find a way to harness the energy of the more progressive base while also battling in states where the party has lost ground to Trump.

“If the Democrats can’t compete in the Midwest and the Great Plains, then the path back to majority is going to be a long time coming,” said Sen. Mark Warner, a Virginia Democrat who is expected to run for reelection in 2026.

Democrats will be defending seats in 2026 in states like Michigan, New Hampshire and Georgia, with few potential pickup opportunities outside of Maine and North Carolina.

But Peters, the former chair of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, argues that even as he leaves behind one of the toughest battleground seats Democrats have on the map, the political climate for the president’s party in a midterm year will give Democrats a built-in advantage.

“We’ve got a new president. He’s already creating a great deal of chaos. I’m confident we’re gonna have a lot of backlash next year,” he said. “It’s gonna be a good Democratic year.”

With the work in Washington dwindling for dealmakers, the personal costs of the job – something not often discussed because such complaints risk criticism for complaining or being out of touch – were a factor for the trio as they deliberated.

The Senate commute requires several days each week away from home, trekking through airports and racing to votes. There is little predictability of knowing when a senator will or won’t be back in their home states, and their schedules are filled often to the brim with meetings, votes and fundraising that sucks even the odd hours of their weeks in Washington.

“I’ve got the luxury of living close,” Warner said. “I am not going to condemn anybody. This is a hard job … no whining on the yacht, but I completely understand people’s personal pressures, family pressures.”

Each of the retiring Democrats talked at length about that toll. On the one hand, they were clear their jobs were hard-earned and an honor to carry out, and yet, each were clear there is a cost.

Shaheen, for example, planned after an overnight voting marathon to try and meet her family in Boston for a benefit – which her entire family would be attending with or without her (she made it to the event).

Smith made her decision to retire when she finally had both of her sons for the first time in years living back in Minnesota with her grandkids.

And all three senators – two in their 60s and one in her late 70s – have watched as aging colleagues missed out on final precious years at home to live out their final days in office, sometimes in decline.

“I will say that watching colleagues who don’t have the same energy and the same drive that they did even seven years ago is something that I for sure notice,” Smith said. “And of course, we all watched with such sadness as we saw Sen. Feinstein become a shadow of the dynamo that she was.”

While none of the lawmakers had clear plans on what they would do next, each noted they had at least a hobby or two they looked forward to returning.

“I’m not sure exactly what all the chapters will be, but one of those chapters will be riding my Harley Davidson on a twistin’, turnin’ road and with the wind in my face,” Peters said.

For the senators in the middle who remain, the departure of more colleagues willing to make deals makes things even tougher.

Sen. Lisa Murkowski – the Alaska Republican who famously fought off a primary challenge in 2010 to win a write-in campaign in the general election – ticked off the Indian Affairs legislation she worked on with Smith and the Arctic and women’s issues she’s tackled with Shaheen.

“I’ve already told Jeanne Shaeen, ‘Please don’t leave!’” Murkowski said with a laugh.

Murkowski pointed to the infrastructure bill in the last Congress as an example where the group of senators that came together ultimately found the negotiations rewarding – and a way to put forward good policy for the country.

“You have to demonstrate that it can be done and you’re not going to be beaten up by your base for fraternizing with the enemy – although sometimes you’re still going to be beaten up for it,” she said. “But you have to know that the outcome is worth the criticism that you’re going to sustain.”

For Democrats, opposing Trump’s sweeping attempts to remake the federal government and American institutions has provided a cause to rally behind – but it’s also sparked frustration from within the party because in many cases, there’s little Democrats can do but protest.

“I just think that right now in the Senate, it’s really, really hard for those folks, being in the minority, to do anything to hold people accountable,” Tester told CNN. “This has been a rubber stamp Congress so far. I’ve worked with a lot of those folks, they’re good people that know better. That’s what pisses me off.”

Warner, who played a key role in the infrastructure talks in the last Congress, argued that “radical centrists” like him – willing to listen on all issues – are vital to the Senate.

“If you don’t have the hope piece, this is pretty bleak,” Warner said.

Smith said she remains confident that even if she’s leaving an open seat behind in Minnesota, a Democrat can win the race to replace her and come to Washington with energy to help make the Senate better.

“This is an incredible, amazing, powerful job and it’s been incredible to do this job, but I am not burdened by the idea that I am the only one who can do this,” she said. “I actually am energized by the idea of making space for the next great leader to step into the role.”

CNN’s Morgan Rimmer contributed to this report.